Hepatitis A, B, and C Surveillance, Allegheny County, 2022

Hepatitis A

Introduction

Hepatitis A is a vaccine-preventable liver infection caused by the hepatitis A virus. People who get hepatitis A don’t always have symptoms, but those who do may experience symptoms like jaundice, stomach pain, nausea, and diarrhea for a few weeks or months. Most people recover completely from hepatitis A and do not have lasting liver damage. In rare cases, hepatitis A can cause liver failure and even death; this is more common in older people and in people with other serious health issues, such as chronic liver disease.1

Hepatitis A is highly contagious virus found in an infected person’s blood or feces. Most often, it is spread through close personal contact, such as through certain types of sexual contact, caring for someone who is ill, or using drugs with others. Although uncommon in the United States, hepatitis A can also spread by eating contaminated food.1

Hepatitis A usually goes away on its own. Most doctors advise people with hepatitis A to rest, get adequate nutrition, and drink plenty of fluids. In severe cases, patients may have to receive medical care at the hospital.1

Hepatitis A Infection

Cases of hepatitis A are rare in the United States. According to CDC, there were a total of 5,728 hepatitis A cases reported in 2021 nationwide.1 However, because not everyone has symptoms or gets diagnosed, the actual number of cases occurring in that year was probably closer to 11,500.1 Cases in the US increased from 1,390 cases in 2015 to 5,728 cases in 2021, with outbreaks occurring most often among people who use injection drugs or experience homelessness.1,2

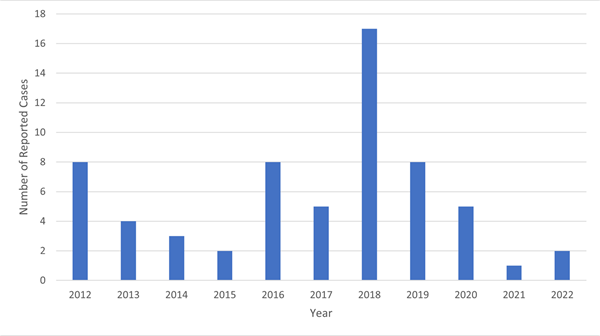

Allegheny County saw the highest number of hepatitis A cases in 2018, when 17 cases were reported, but since then the number of cases has been low. In 2022, there were only two reported cases in Allegheny County (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Reported confirmed hepatitis A infections by year, Allegheny County, 2012-2022

Prevention

The best way to prevent hepatitis A is by getting vaccinated. While childhood vaccination against hepatitis A has been routine since 2006, many adults have not received the vaccine and may be at risk for severe disease. Although hepatitis A is very contagious, you can take the following steps to prevent infection:

- Get vaccinated against hepatitis A

- Wash your hands with soap and water after using the bathroom, changing diapers, and before preparing, serving or eating food

- Don’t share food, drinks, or smoking products with other people

- Avoid eating raw oysters

- Do not share towels, toothbrushes and eating utensils

- Don’t have oral-anal sex with someone who has hepatitis A

Resources

https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hav/pdfs/hepageneralfactsheet.pdf

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, July 28). What is hepatitis A - FAQ. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2021surveillance/hepatitis-a/figure-1.1.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 27). 2021 Viral Hepatitis Report. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2020surveillance/hepatitis-a.htm

Hepatitis B

Introduction

Hepatitis B is a vaccine-preventable liver infection caused by the hepatitis B virus. It is spread by contact with bodily fluids through sex, IV drug use, or from mother to baby at birth. Hepatitis B infections can be either acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term).

Most healthy people recover from acute hepatitis B without treatment, but acute hepatitis B can sometimes lead to life-long infection known as chronic hepatitis B. Infants and young children are most likely to develop chronic hepatitis B if infected.1 About 25 percent of people who become chronically infected during childhood, and about 15 percent of those who become chronically infected after childhood will eventually die from serious liver conditions.1

Currently, there is no treatment available for acute cases of hepatitis B, but people with chronic hepatitis B infections may be prescribed medication if symptoms are severe.

Vaccination remains the best method of preventing hepatitis B infections.

Acute Hepatitis B

Acute hepatitis B is a short-term illness that occurs within six months after exposure. Symptoms can include fatigue, poor appetite, stomach pain, nausea, and jaundice, but not everyone experiences symptoms. Only 30 to 50 percent of people over five years old will have symptoms when newly infected with hepatitis B, and most children under five have no symptoms.1

Because many people with acute hepatitis B do not experience symptoms, CDC estimates that the true number of cases is much higher than reported. In 2021, CDC said that there were 2,045 reported cases of acute hepatitis B, but an estimated 13,300 infections nationwide.2

In 2022, Allegheny County had two reported cases of acute hepatitis B.

Chronic Hepatitis B

Although there is no treatment for acute hepatitis B, most healthy adults (between 94 and 98 percent), and some infants (10 percent) clear the infection with no lasting effects.3 Infants, young children, and immunosuppressed persons with acute hepatitis B are most likely to develop a chronic hepatitis B infection. Chronic hepatitis B is a life-long infection that can cause serious health problems, including liver damage, cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death.1

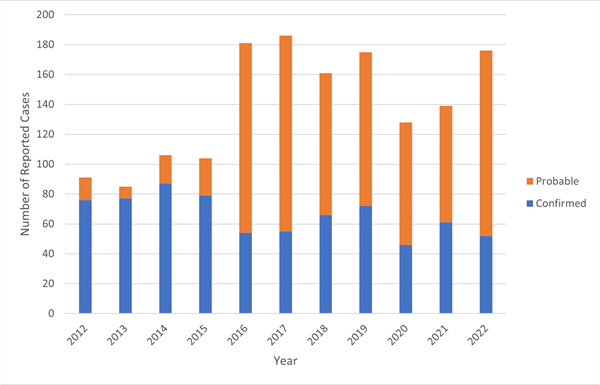

In 2022, there were 52 confirmed cases of newly diagnosed chronic HBV reported in Allegheny County, for a crude incidence rate of 4.2 per 100,000, lower than the state rate of 6.1 per 100,000 in 2021.4 That same year, there were 124 probable** cases of chronic hepatitis B in Allegheny County.

Figure 1: Newly reported confirmed* and probable** chronic hepatitis B infections by year, Allegheny County 2012-2022

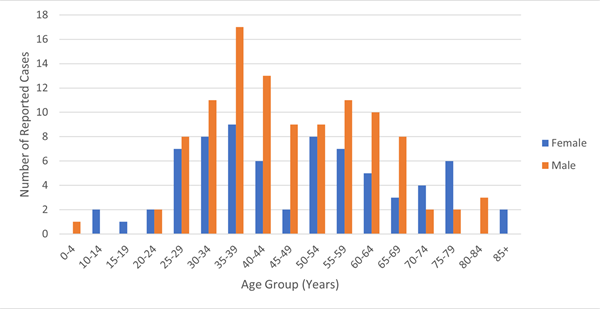

Of the 176 confirmed and probable cases, 72 (41%) were females, and 104 (59%) were males. The 35-39 year-old age group had the most cases reported (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Newly reported confirmed* and probable** chronic hepatitis B infections by age group and sex, Allegheny County, 2022

*A confirmed case of chronic hepatitis B is defined as:

- Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen (IgM anti-HBc) negative AND a positive result on one of the following tests: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), or nucleic acid test for hepatitis B virus DNA (including qualitative, quantitative and genotype testing), OR

- HBsAg positive or nucleic acid test for HBV DNA positive (including qualitative, quantitative and genotype testing) or HBeAg positive two times at least 6 months apart (Any combination of these tests performed 6 months apart is acceptable)8

**Probable cases of hepatitis B are not nationally notifiable but are included in this report in line with PADOH’s annual report. A probable case of chronic hepatitis B is defined as: a person with a single HBsAg positive or HBV DNA positive (including qualitative, quantitative and genotype testing) or HBeAg positive lab result and does not meet the case definition for acute hepatitis B.8

Perinatal Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B infection can pass from mother to infant at birth, but transmission can be prevented by providing hepatitis B immune globulin and hepatitis B vaccine to infants within 12 hours of birth. According to CDC, without intervention, approximately 40 percent of infants born to infected mothers will develop chronic hepatitis B infection.5

In 2022, there were 23 infants born to mothers with chronic hepatitis B infections in Allegheny County. Of these infants, all 23 received hepatitis B immune globulin and hepatitis B vaccine. To date, no infant developed a hepatitis B infection.

Hospitalizations Associated with Hepatitis B

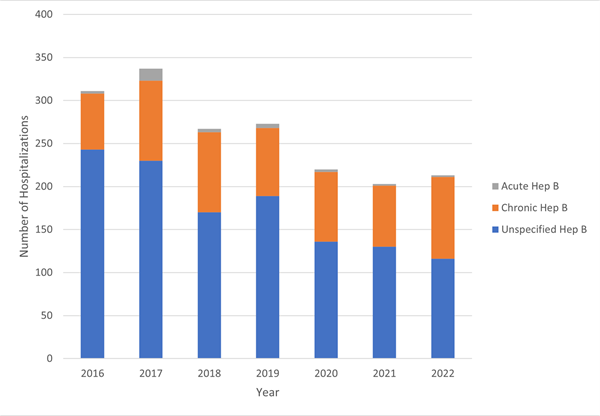

Depending on the severity of symptoms, hepatitis B infections may lead to hospitalization. Most people who have hepatitis B go to the hospital for other ailments, which may be complicated by their hepatitis B infection. In 2022, 213 people in Allegheny County were hospitalized with a primary or secondary diagnosis of hepatitis B. Of these, 211 (99%) had chronic or unspecified hepatitis B, and two (1%) had acute hepatitis B (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Hepatitis B-related hospitalizations, Allegheny County residents, 2016-2022

Data source: Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council

Among the 96 women who were hospitalized in 2022 with a diagnosis of hepatitis B, 28 (29%) were 60-69 years of age (Figure 4). The median age for hospitalized women was 59 years, with a range 24-89 years, compared to a median age of 63 years for hospitalized men, with a range of 25-92 years.

In 2022, pregnancy related concerns were among the most common primary diagnoses of people hospitalized with hepatitis B. These cases accounted for 18 percent of all hepatitis B related hospitalizations in women.

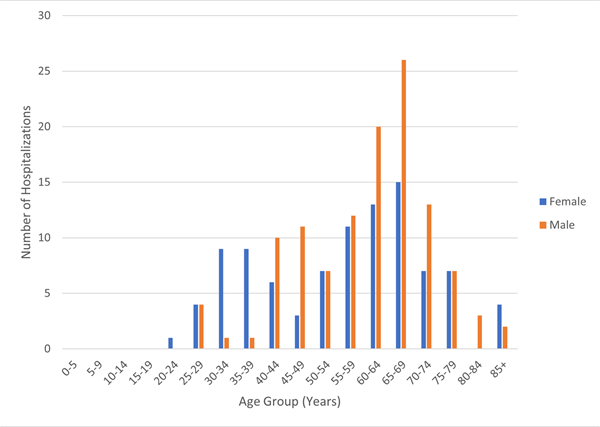

Figure 4: Hepatitis B-related hospitalizations by age group and sex, Allegheny County, 2022

Data source: Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council

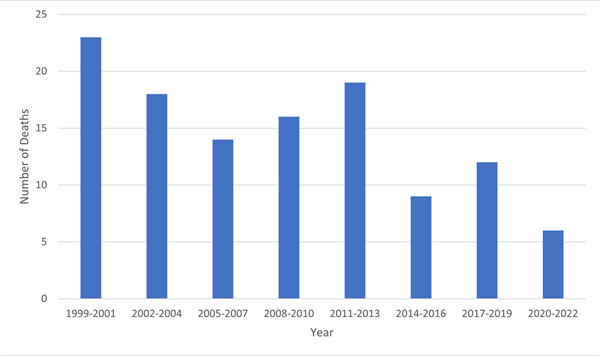

Deaths Associated with Hepatitis B

From 2020 through 2022, a total of 6 people in Allegheny County had hepatitis B listed as an underlying or contributing cause on their death certificate. Deaths attributed to hepatitis B have decreased since the 2011 – 2013 timeframe (Figure 5).6

Figure 5: Number of deaths with hepatitis B listed as a cause of death, 1999-2022

Data source: CDC Wonder6

Prevention

The best way to prevent Hepatitis B is to get vaccinated. CDC recommends that all infants and adults under 60 get vaccinated against hepatitis B. If you haven’t been vaccinated, or if you’re unsure if you have been vaccinated, talk with your doctor or visit ACHD’s Immunization Clinic.

CDC also recommends all people over 18 years old get tested for hepatitis B at least once in their lifetime.

Other ways to prevent hepatitis B:

- Never share needles

- People who use intravenous drugs are at high risk of getting infected with hepatitis if they share needles or other equipment

- Avoid direct exposure to blood or blood products

- Any tools that encounter blood or draw blood should be disposed of safely or sterilized

- Don’t share personal care items

- Sharing razors or toothbrushes can also be a vehicle for viral transmission since small cuts sometimes occur on the skin or gums during use

- Avoid getting a tattoo or piercing

- If getting a tattoo or piercing, ask the artist about their sanitary procedures, such as using new disposable needles and ink wells for each customer and properly using an autoclave for non-disposable supplies.

- Practice safer sex

Resources

References:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, March 30). Hepatitis B frequently Asked Questions for the Public FAQ. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/bfaq.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, August 7). Hepatitis B Surveillance 2021. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2021surveillance/hepatitis-b/figure-2.1.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, March 13). Hepatitis B - Vaccine Preventable Diseases Surveillance Manual | CDC. (n.d.). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/surv-manual/chpt04-hepb.html#

- Pennsylvania Department of Health. Enterprise Data Dissemination Informatics Exchange (EDDIE). Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://www.phaim1.health.pa.gov/EDD/WebForms/CommDisSt.aspx

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, April 16). Hepatitis B, chronic 2012 case definition. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved October 19, 2022, from https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/hepatitis-b-chronic-2012

- “Perinatal Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 16 Feb. 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hbv/perinatalxmtn.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released in 2021. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2020, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd-icd10.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B, Chronic 2012 Case Definition. Retrieved Dec 6 from: https://ndc.services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/hepatitis-b-chronic-2012/

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is a liver disease that results from infection with the hepatitis C virus (HCV), which is spread primarily through contact with the blood of an infected person. Hepatitis C infection can be classified as either “acute” or “chronic.” Cases are referred to as “acute” if the infection is newly acquired. Acute infection generally leads to chronic infection, as only 15-25 percent of persons clear the infection without treatment. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) states that today most people become infected with HCV by sharing needles or other equipment to inject drugs. Effective medications are available to treat the disease with few side effects. Treatments usually involve 8-12 weeks of a one-pill-a-day regimen and result in a cure for over 90 percent of infected individuals.

Acute Hepatitis C

Persons with acute hepatitis C infections often do not have symptoms; however, 20-30% of individuals have mild to severe gastrointestinal symptoms, including jaundice, within six months of infection. Identification of acute cases requires symptom information and laboratory data or evidence of seroconversion. In 2022, 17 cases reported to the Allegheny County Health Department met the revised 2020 acute case definition.* Of these, 16 were classified as confirmed acute cases and 1 was classified as a probable acute case. The CDC estimates that the true number of acute cases is much higher than what is reported each year.1

Chronic Hepatitis C

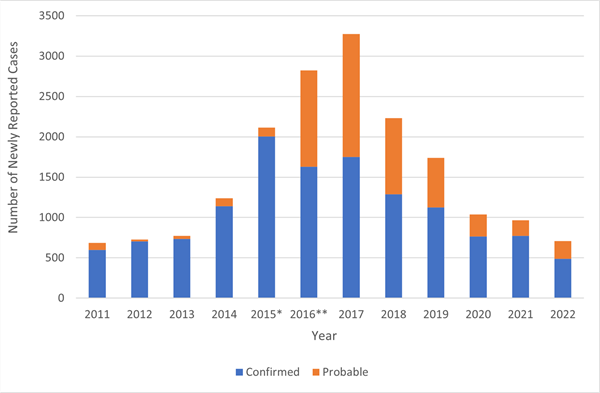

Chronic hepatitis C is associated with liver damage and sometimes liver failure or liver cancer. The number of newly reported chronic hepatitis C cases in Allegheny County has been decreasing since 2017. The trend from 2021 to 2022 was no exception. The reason for the decrease is uncertain, given the disruption in health care testing services during the COVID-19 pandemic.2,3 In 2022, there were 709 cases of chronic hepatitis C cases reported among Allegheny County residents. Of that total, 487 (69%) were classified as confirmed chronic cases** and 222 (31%) were classified as probable chronic cases*** (Figure 1).

* The number of reported acute cases was determined using the 2020 CSTE Acute Hepatitis C case definition. A probable acute case is classified as a case that meets clinical criteria and has presumptive laboratory evidence AND does not have a hepatitis C virus detection test reported AND has no documentation of anti-HCV or HCV RNA test conversion within 12 months. A confirmed acute case is classified as a case that meets clinical criteria and has confirmatory laboratory evidence, OR a documented negative HCV antibody followed within 12 months by a positive HCV antibody test (anti-HCV test conversion) in the absence of a more likely diagnosis, OR a documented negative HCV antibody OR negative hepatitis C virus detection test (in someone without a prior diagnosis of HCV infection) followed within 12 months by a positive hepatitis C virus detection test (HCV RNA test conversion) in the absence of a more likely diagnosis.

** Chronic cases are considered confirmed if a person has a positive HCV NAT, HCV antigen, or genotype result without clinical information consistent with acute infection

*** Chronic cases are considered probable if a person has a positive HCV antibody test but no confirmatory test and no clinical information consistent with acute infection

Figure 1. Chronic hepatitis C cases by year and classification, Allegheny County, PA, 2011-2022

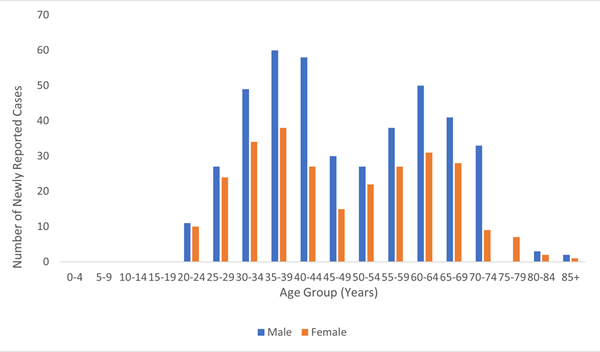

Of the 709 confirmed and probable cases in 2022, 429 (61%) were male and 275 (39%) were female. The remaining 5 cases (0.7%) were classified as sex unknown. The age distribution was bimodal with peaks in the 30-44 year and 55-69 year-old age groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Chronic hepatitis C cases by age group and sex, Allegheny County, PA, 2022

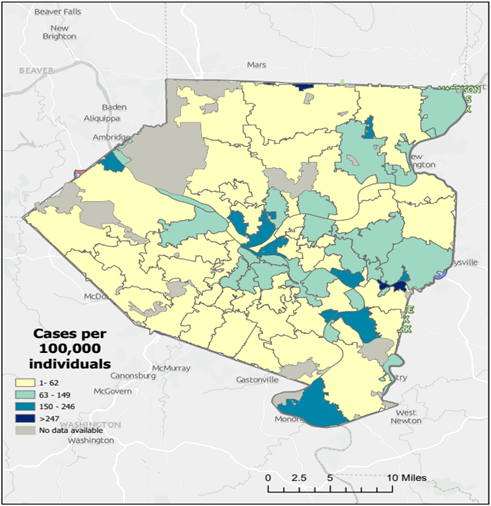

The rate per 100,000 of newly reported chronic HCV cases in Allegheny County is shown below by zip code of residence (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Newly reported chronic hepatitis C cases per 100,000 population by zip code of residence, Allegheny County, PA, 2022

Perinatal Hepatitis C

The hepatitis C virus can be transmitted from an infected mother to her infant at birth. Mother-to-child transmission is the leading cause of childhood HCV infection. According to the CDC, the number of infants born to women who are infected with HCV is increasing. The CDC recommends HCV testing during every pregnancy so that infants at risk of infection receive appropriate testing and care. In 2022, one case of perinatal HCV was reported in Allegheny County. Women with active HCV infections are encouraged to seek treatment prior to becoming pregnant.

Hospitalizations Associated with Hepatitis C

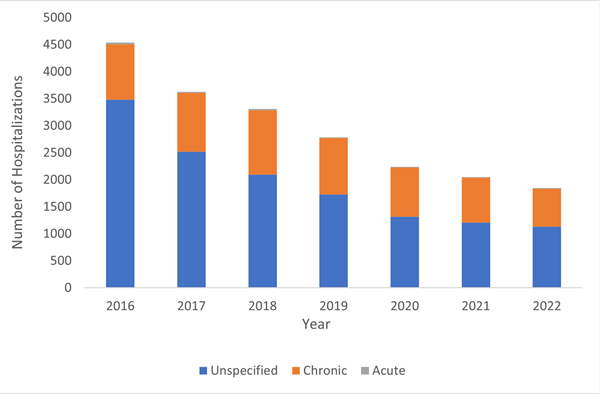

Depending on the severity of illness, hepatitis C infection can result in hospitalization. In 2022, 1,832 people were hospitalized with a diagnosis of hepatitis C either as a primary diagnosis or a secondary diagnosis (Figure 4). From 2021 to 2022, the number of HCV hospitalizations decreased by 10 percent. The percentage of all hospital admissions in Allegheny County in 2022 with an HCV diagnosis was 1.4% and has been decreasing since 2016.

Figure 4. Hospitalizations with an HCV diagnosis, Allegheny County, PA, 2016-2022

Data source: Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council

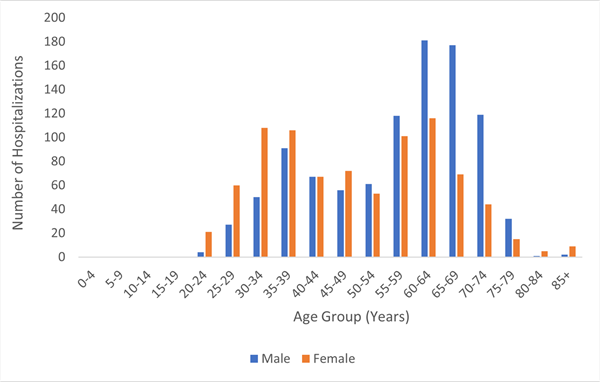

Of all HCV-related hospitalizations, 986 (54%) were among males. Of hospitalized males, the median age was 60 years, with a range of 22-87 years. A large proportion (36%) of males hospitalized with a diagnosis of hepatitis C were between 60 to 69 years of age. Of 846 hospitalized females, the median age was 48 years, with a range of 21-96 years (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Hospitalizations with an HCV diagnosis by age group and sex, Allegheny County, 2022

Data source: Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Council

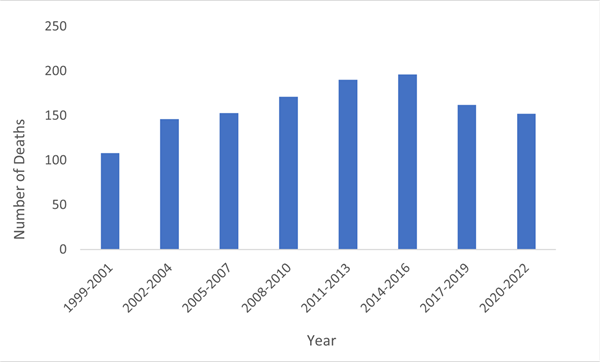

Hepatitis C-related Mortality

From 2020 through 2022, a total of 152 people in Allegheny County had hepatitis C listed as an underlying or contributing cause on their death certificate. Deaths attributed to hepatitis C have decreased since the 2014-2016 time period (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Number of deaths with hepatitis C Listed as an underlying or contributing cause, 1999-2022

Data source: CDC Wonder

Hepatitis C Prevention

Hepatitis C is the most common bloodborne infection in the United States. It is spread through exposure to the blood of someone who is infected. Exposure to even a small amount of blood is enough for a new infection to occur. Here are steps to prevent infection with HCV:

- Never share needles or equipment to inject drugs

-

- People who use intravenous drugs are at highest risk of getting infected with HCV because many share needles

- Wear personal protective equipment when working with blood or blood products

-

- Any tools that come into contact with blood should be disposed of safely or sterilized

- Don’t share personal care items

-

- Sharing razors or toothbrushes can also be a vehicle for HCV transmission given that small cuts sometimes occur on the skin or gums during use

- Use professional tattoo/piercing services

-

- Correct sanitary procedures, such as using new disposable needles and ink wells, should be followed for each customer

- Practice safe sex

-

Hepatitis C Treatment

Direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatment is available and highly effective for treating HCV infection and cures approximately 95 percent of cases.4 It is recommended for almost all individuals with HCV infection. Recent data shows that of those diagnosed with HCV, only 1 in 3 with insurance receive timely treatment.4 Individuals on Medicaid were 46 percent less likely to receive treatment than those with private insurance.4 Furthermore, Medicaid recipients identifying as Black or other race were 27 percent less likely to get timely treatment than white Medicaid recipients.4 To reduce HCV-related morbidity and mortality, quickly linking identified cases to treatment is crucial.

Resources

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2018). Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report 2019. Retrieved from: Hepatitis C Surveillance in the United States for 2019 | CDC. April 28, 2023

- Kaufman HW, Bull-Otterson L, Meyer WA, Huang X, Doshani M, Thompson WW et al. Decreases in Hepatitis C Testing and Treatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic. AJPM 2021;61(3): 369-376.

- Barocas JA, Savinkina A, Lodi S, et al. Projected long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hepatitis C outcomes in the United States: a modelling study. Clin Infect Dis. Published online September 9, 2021. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab779

- Thompson WW, Symum H, Sandul A, et al. Vital Signs: Hepatitis C Treatment Among Insured Adults — United States, 2019–2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71:1011-1017. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7132e1.